In honor of the news that the folks at Drag City are hard at work on a documentary about the Red Krayola’s Mayo Thompson, I’m reposting an interview Susan and I did with him for the print version ofWarped Reality. 1995 was a veritable Summer of Red Krayola, with a whole slew of reissues courtesy of Dexter’s Cigar (including Thompson’s effortlessly charming solo debut, Corky’s Debt to His Father), and culminating in the first RK tour in a small forever.

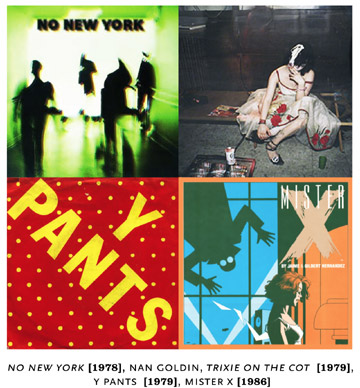

The leader of ever-shifting musical collective RK (née Crayola, until a certain corporation got wind of it) has led the band through numerous incarnations (and initial public indifference) since 1968. From such humble beginnings as part of the Texas psych underground, Thompson slowly but surely forged ahead on his own deeply idiosyncratic path, collaborating with a stunning array of like-minded individuals along the way (Pere Ubu’s David Thomas, Jim O’Rourke, Albert Oehlen, David Grubbs, Gina Birch, Lora Logic, Epic Soundtracks, John McEntire —the list could go on and on) and becoming stealthily legendary. Thompson’s wry, philosophically pithy songs have influenced a whole generation of songwriters (Exhibit A: the majority of the Drag City roster).

Without further ado, the interview. I’ve left the original intro intact.

[Originally published in Warped Reality #3, 1995. Interview conducted in the front room at the Middle East Café, Cambridge MA.]

***

Picasso once said that “the true artist is never experimental. Experimentation is for those who don’t know what they’re doing.” Mayo Thompson, the founding member and only constant in the ever-shifting line-up of Red Krayola, would easily fit Picasso’s definition of a true artist. Since Red Krayola formed in

the early 60s, Thompson has braved general indifference (and outright scorn) to his work. But now, thanks to Drag City’s reissue of Thompson’s 1970 solo record, Corky’s Debt to His Father, and a brand-new self-titled Red Krayola album, Thompson is being rediscovered.

He’s garnered a devoted, if small, following over the years. Galaxie 500 covered one of his songs. He’s played with Pere Ubu and he produced the Raincoats’ debut album, but Thompson’s own work is in a style all his own, descended from no-one, even if he currently shares stylistic territory with Thinking Fellers Union Local 282 or his label-mates at Drag City.

He’s garnered a devoted, if small, following over the years. Galaxie 500 covered one of his songs. He’s played with Pere Ubu and he produced the Raincoats’ debut album, but Thompson’s own work is in a style all his own, descended from no-one, even if he currently shares stylistic territory with Thinking Fellers Union Local 282 or his label-mates at Drag City.

Thompson himself laughs about the fact that he’s always pegged as “that psychedelic guy from the 60s” —that is, some relic who’s been written off because a writer didn’t understand him. But Thompson’s music remains relevant and invigorating, especially in these post-grunge days when music continually seems to be getting more formulaic. (And it would only get worse from there… —Ed.) Thompson’s songs trade in lyrical absurdities, but there is a spareness and a concision to all his songs. He is deeply interested in abstractions and playing with forms and contexts, but what concerns him first and foremost are human interactions and emotions. It’s fitting, then, that the opening line of ) Corky’s Debt is “I’m a student of human nature,” a possible statement of intent for all of Thompson’s work.

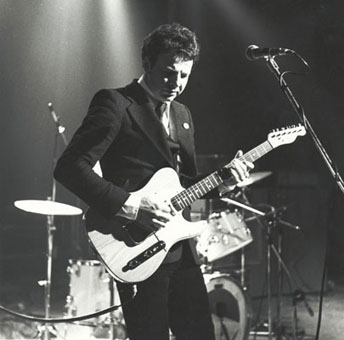

Thompson and his band, comprised of David Grubbs and John McEntire of Gastr del Sol, and ex-Minutemen drummer George Hurley, made a short jaunt to the East Coast recently, Thompson’s first here since the 60s. We were lucky enough to be able to talk to Thompson before the show, and even luckier to witness the reborn Red Krayola.

What led to the formation of the Red Krayola, back in the 60s?

MT: I was interested in writing, I was interested in film. I was interested in all sorts of things. And we just looked around at what was going on in the arts, and writing continued to be dominated by the modernist, high-modernist school. And then there were the modernist offshoots, like Beckett. So there was an official avant-garde culture and there was a mainstream culture, and one didn’t fit in either place very well. And one wanted to make tokens or “things” without being so precious about it. So, without trying to make the most beautiful bloody painting that had ever been made, not to try to make the most romantic, gorgeous, heart-rending blah, blah, blah. Not to aspire to these ideals, but just to find out if there was anything to say in relation to these forms. And, if anything could be said with these forms, what could that possibly be? So music was an instrumentality that hadn’t been tried by us. Went to Europe in ’65. Came back and was convinced that the only thing for us to do was start a band because the most possibilities were there.

So that’s how we started —with the idea that yes, music has got something to do with human spirit and all these [modes] of meaning. Quickly finding out that it doesn’t have much to do with that. That everything has got to do with that, and nothing has to do with that. The process of actually saying something that makes sense to somebody else is fairly complicated. It means that if I make something, one person finds it interesting, another person finds it pretentious bullshit, and another person finds it completely, “Huh? What the fuck is that?” There are so many possible responses, as many as there are people. Bit by bit one gathers together the pieces of the puzzle, of what it means to produce something in what we call “real life.” What you would call “warped reality”, probably. And I’m inclined to agree with you. It is bloody warped, and wide open.

When people start talking metaphorically about things, maybe I get it, maybe I don’t. Or I can understand the metaphor, but that doesn’t mean I necessarily know what they think of the music or how they feel about it. So I’m very interested in this problem of how you try to put it into language. Artists make these sacred objects and we’re just supposed to stand there in relation to them and go “ooh.” I just don’t have that kind of relationship to it myself and I can’t imagine anybody else does either. Why should it just be this un-analyzed, irreducible lump? The relationship must be constructed somehow. I’m not interested in deconstruction for its own sake, but I wouldn’t mind defacing it a little bit.

One thing I have found out is that expressing oneself is something I can’t stop doing, and only some people are going to get it, and other people will say things like “quirky weirdness,” but I just happen to be interested in abstraction and abstraction is the sphere in which I can most adequately deal with the numbers of things that are in play. Because certain kinds of statements you can make strong. You can say “Fuck you!” to the world and everybody understands exactly what that means, depending on the tone of voice.

But it still depends on tone of voice…

MT: Exactly. So then you find out that by modulating the tone of voice, you introduce some kind of uncertainty into the equation, some instability. Part of the game is to find out what it : means to say certain things, and finding new ways of twisting it around, having fun, and keeping it interesting and alive.

The business system in America encourages you to get yourself into some little niche, and work it, like a little gold mine. I’m the guy who does “psychedelic music from the 60s.”

I am genuinely, seriously interested in learning. That’s one of the reasons I continue to do this. There’s a whole new generation of people who are solving problems for themselves in new ways. We all learn from each other, I hope. We’d better.

Or we’re in trouble.

MT: Oh, we’re in trouble anyway. People tell me I’m a bit cynical. Pessimistic, definitely. Cynical, maybe not. I think that cynicism is inexcusable though, because it’s knowledge without paying the price. It’s knowing and being satisfied with knowing.

Making music is a strange process. One of the things I like about it is that it puts you in so many different states of mind at the same time. It has a movement of its own, a dynamic. It just goes. And with music you can think out loud. Some people say it’s a little world. I think good records do draw you in.

Were you a fan of the Residents?

MT: I was, definitely. I don’t know them. I met one of them years and years ago in London. But somehow I’ve lost touch. I lived in Europe for 18 years. So my contact with the Residents was minimal. I haven’t got all my records in one place at the moment. I’ve got stuff in storage in Germany and in England.

So where are you living now?

MT: In a suitcase!

What happens when the tour ends?

MT: Wherever my suitcase gets dropped I wait for it to go someplace and I follow it. I’m actually going to teach in Los Angeles for three months.

What kind of feedback did you get at earlier shows?

MT: Audiences were appropriately or politely interested. “OK, what’s next?” ‘cause it was pop music, it’s disposable. Now, the chance to come back and play some of these ideas which have been going for a very long time —playing songs from the very beginning, playing songs that are a couple of months old, a whole range of material— is quite interesting. To take all that potential and try and bring it to life in one night is a challenge. Because the music just exists in this potential state, it’s all notated. It exists on paper and in the brain and in the talents of all the people who bring it to life.

Or it exists on the record, which is a perfect, static entity.

MT: And it is a record. It’s a record of what we were able to do with that piece of music at that time. But everybody comes together and makes something happen here tonight and we’re all part of this process. Hopefully we all get something fun out of it.

Really, this is the assault on America. Never have tried this before. Tried 28 years ago when we started the band in Texas and then took the idea that art had something to do with the process, that you could take so-called “serious ideas” into the process and took seriously that there was an idea of progress, that music actually led to some conclusion. So I took the logic of popular music and it seemed to lead to feedback. It seemed to lead to the idea of the electric guitar leaning against the amplifier.

When you come to a place like this to make a spectacle of yourself, it should be fun. There is this kind-of exchange with the audience, who have the final say in everything. Once I’ve made something, my opinion is no better than anyone else’s.

You don’t have to be actively creative. Thinking is a creative process. Life is a series of mind-numbing, dumb processes and a series of frustrations, and all you have is your stupid desires, your stupid frustrations. At the end of it, I think I’d get pretty pissed off myself, if I weren’t so lucky to have such a pleasant and privileged job. I mean, hell, I am pissed off, even though I have such a nice job.

How did you get the name Warped Reality? Is there an aspect of reality which is unwarped?

Doubtful.

MT: I agree. There’s only one reality. Well, you can make it up. There is irreality. There is not only one truth. We could talk about context. We could talk about Red Krayola in the context of underground rock music. Like, why don’t we have anything to do with Brian Eno?

Or why doesn’t Michael Stipe sing backing vocals?

MT: That’s another level! I want to operate on that level, I think. Stadium rock.

Red Krayola arena tour!

MT: Don’t you think that would be good?

Yeah, people with lighters!

MT: I want to see that. I want to look out into a sea of butane.

Sweaty bodies, mosh pits!

MT: People singing “The Labor Theory of Value” as they smash into each other!

It’s interesting since we were talking a bit earlier about how the Raincoats’ time has come around again and the same is true of your music.

MT: Right now, there’s a time when everything is up for grabs again. Nobody knows for sure what anything is worth. Some things are open, particularly on the turf that we’re on. There are infinitely many ways of skinning a cat, so there are definitely many alternative ways of making music. And now is the time to do this again. And the first line of defense against music that operates on a popular scale is the music business. Like, once you’ve conquered the hearts and minds of the music business, then you’re allowed to make music for people.

***

Mayo Thompson is working on a new, as-yet-untitled Red Krayola album, for release on Drag City next year. Until then, you can watch the waves over at the official Red Krayola site.

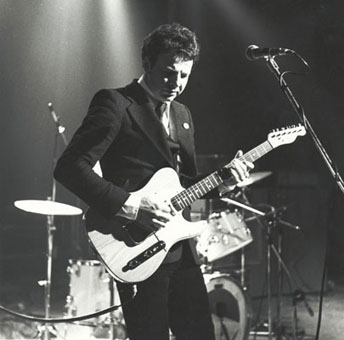

![]() Ruth, Mots

Ruth, Mots